The Business of War

When war breaks out, so do the slogans — how brands navigate the battlefield of consumer trust.

When the bombs fall, the slogans rise. Wars have long been fertile ground for commercial marketing—not just government propaganda. From Coca-Cola bottling plants in WWII to logo-lit tributes in Ukraine, brands have historically used wartime to reaffirm their values, solidify customer loyalty, or expand into new markets.

This article explores how brands have engaged in wartime marketing across several major conflicts. These campaigns range from supportive and strategic to controversial and opportunistic, revealing how commerce adapts to conflict.

World War II: Selling Sacrifice and Building Brand Loyalty

World War II marked the beginning of large-scale brand involvement in wartime communications. Due to rationing and production shifts, many consumer goods were unavailable to the public. Nevertheless, companies continued to advertise with patriotic messages, often aimed at maintaining brand loyalty during and after the war.

Coca-Cola promised to provide every U.S. soldier with a bottle of Coke for five cents, leading to the construction of bottling plants near battlefronts. This initiative not only supported troop morale but significantly expanded the company’s global reach. By war’s end, Coke had become an international brand.

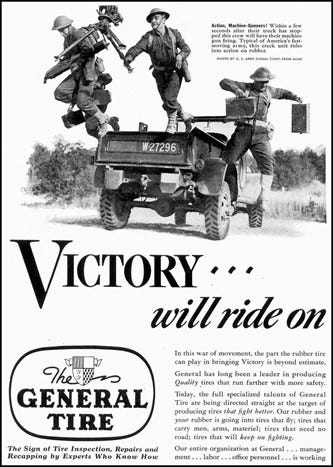

General Tire ran ads telling consumers not to buy tires to conserve rubber. Instead, they encouraged Americans to buy war bonds. Other companies like General Motors and Bell & Howell advertised their military equipment, not for civilian sales, but to associate themselves with the war effort.

These campaigns were not driven solely by altruism. Companies saw them as long-term investments. By showing their commitment to national causes, they hoped to earn consumer trust that would translate into post-war market dominance.

The Korean and Vietnam Wars: Silence and Scrutiny

The Korean War saw less overt brand involvement, partially due to the conflict’s limited scale and the lingering impact of WWII campaigns. However, during the Vietnam War, commercial marketing entered a new and more controversial phase.

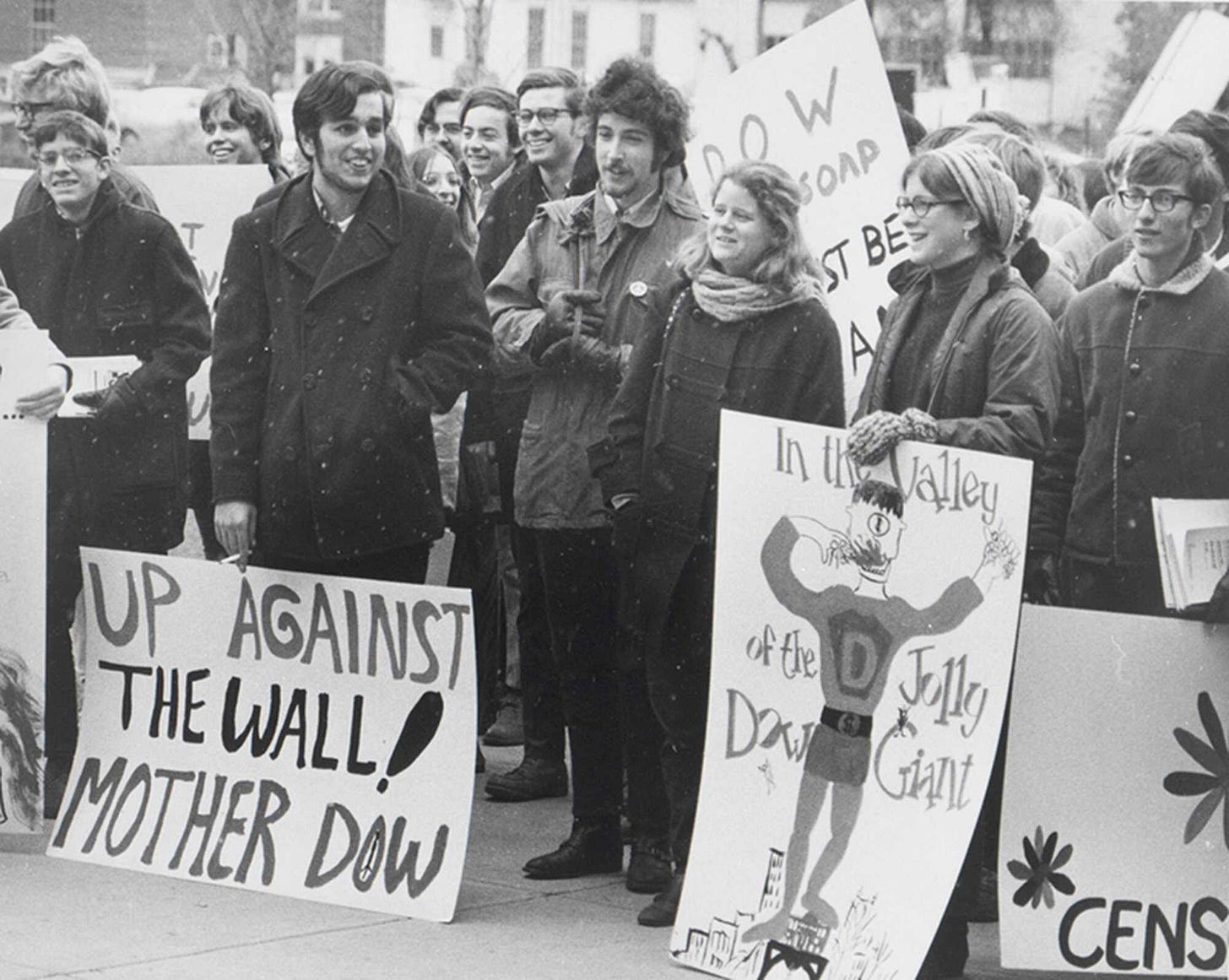

Unlike WWII, Vietnam was widely unpopular and televised. This made overt commercial engagement risky. Most consumer brands chose silence. Exceptions, such as Dow Chemical—producer of napalm—faced backlash. Student protests and negative press coverage damaged Dow’s public image, forcing it to launch PR campaigns to justify its government contracts.

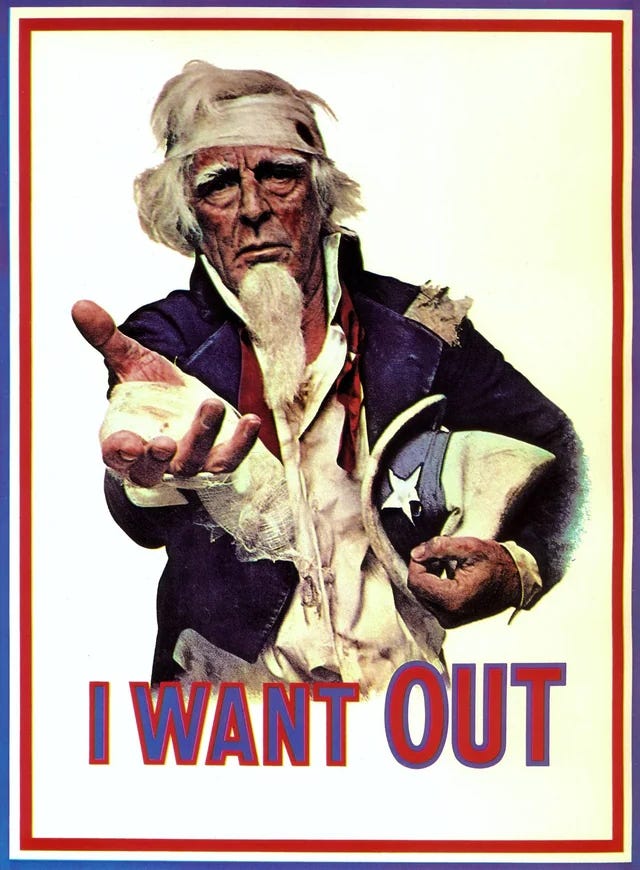

Meanwhile, anti-war activists and artists began to co-opt advertising techniques to deliver counter-messages. They created posters, pamphlets, and parodies using commercial design aesthetics to critique the war and consumer culture.

This period marked the beginning of a more cynical public view of corporate messaging. Brand silence was scrutinised, and corporate involvement in the war effort could lead to reputational harm.

Gulf War (1990–1991): Patriotism and Merchandising

The Gulf War was short, highly televised, and marked by strong public support. Brands responded with visible displays of patriotism. Yellow ribbons appeared on product packaging, and patriotic advertisements became widespread.

Fast-food chains like McDonald’s and soft drink companies like Pepsi and Coca-Cola launched campaigns thanking troops and showcasing American unity. Companies also released commemorative merchandise. Operation Desert Storm-themed products included everything from trading cards to model tanks.

CNN, then a relatively young network, capitalised on its round-the-clock war coverage, significantly boosting its brand. Its coverage style became a template for crisis broadcasting.

Some companies offered discounts to military families or donated portions of proceeds to veteran organisations. Though generally well-received, these campaigns were not immune to critique. Critics argued that the commercialisation of war imagery trivialised the conflict and commodified patriotism.

Post-9/11 and the Iraq War: Marketing Patriotism and Fear

After the September 11 attacks, brands across the United States rushed to align themselves with the surge in national unity and grief. American flags appeared in logos. Slogans like “United We Stand” and “We Will Never Forget” were integrated into product packaging, store windows, and advertising campaigns.

Budweiser aired a well-known Super Bowl commercial featuring Clydesdale horses bowing before the New York skyline. Retail chains such as Walmart promoted American-made goods and featured in-store tributes to first responders.

However, some marketing efforts crossed into controversy. A mattress store in Texas released a 9/11-themed sale commercial that was widely condemned and eventually led to the store’s closure. A Walmart in Florida constructed a 9/11 memorial out of Coca-Cola boxes, which was removed following public criticism.

Meanwhile, sports teams were paid by the Department of Defence to host patriotic ceremonies. These included on-field flag displays and veteran recognitions, which were initially perceived as organic tributes. Once exposed as paid sponsorships, the practice raised questions about authenticity in brand messaging.

Ukraine Conflict: Brand Activism and Consumer Pressure

The 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine marked a turning point in how companies engage with geopolitical crises. Almost immediately, Western consumers demanded that brands take a stance.

Large corporations including McDonald’s, Coca-Cola, Apple, and Starbucks suspended or ended operations in Russia. Some did so after facing backlash and boycott threats on social media. Hashtags like #BoycottCocaCola trended globally, prompting rapid shifts in corporate policy.

Airbnb offered free housing for Ukrainian refugees and waived fees for hosts in affected regions. Fashion and tech companies launched fundraisers, with some donating proceeds to humanitarian causes. Others lit their logos in Ukraine’s national colours or released social media posts declaring support.

These efforts were met with mixed reactions. While many were applauded, others were seen as performative. Brands that changed their colours but made no meaningful contributions were accused of virtue signalling.

Online pressure campaigns, real-time consumer feedback, and increased media scrutiny made neutrality increasingly difficult. Companies discovered that silence could be interpreted as complicity, and missteps could go viral within hours.

Ethical Considerations and Public Response

Wartime marketing raises important ethical questions. Can brands meaningfully contribute to national or humanitarian causes during war without exploiting the situation? What is the difference between solidarity and opportunism?

In some cases, brands have used wartime to reinforce positive values, such as community support, resilience, and aid. In others, they’ve faced backlash for appearing to profit from suffering.

Today’s consumers are more critical. Social media enables rapid public response. Lists of companies still operating in conflict zones are circulated widely. Boycotts are organised in real-time. Corporate social responsibility is no longer limited to annual reports—it is judged in the moment, by millions.

Transparency, consistency, and action have become key benchmarks. Consumers expect more than statements—they expect contributions. Brands that donate, offer services, or support displaced communities are often praised. Those that merely post symbolic messages risk reputational damage.

A Final Thought

Commercial marketing during wartime is complex. For some brands, it’s a chance to demonstrate values and contribute to causes. For others, it’s a tightrope walk between visibility and backlash.

As history shows, the best campaigns are those that balance empathy with action. Wartime marketing that genuinely supports affected communities tends to build long-term trust. But when commercial interests appear to overshadow compassion, the damage can be lasting.

In the age of information, consumers are paying attention—not just to what brands say, but what they do. And in wartime, the difference between the two can define a brand for years to come.