If you ever needed proof that marketing can be a bit evil, look no further than the pink tax — the charming little trick where brands slap a pastel label on a product and quietly charge women more for it. No, it’s not an actual government tax. It’s a marketing hustle dressed up as “personalisation.” And for decades, it worked beautifully.

The scam is simple: same product, different colour, higher price. Women have been paying it since long before anyone had the language to call it out — from the razors in your bathroom cabinet to the deodorant stick in your gym bag. In 2025, despite all the “progress” companies love to brag about, the pink tax isn’t dead. It’s just got better PR.

A Brief, Depressing History

The roots of the pink tax go back to the 1990s, when California researchers uncovered a pattern: women were often charged more for everyday services like haircuts, dry cleaning, and car repairs. A 1994 report by the California Assembly Office of Research estimated that women paid, on average, $1,351 more per year than men for comparable goods and services. These findings led to the Gender Tax Repeal Act of 1995, which banned gender-based pricing for services requiring the same time, cost, and skill. But the law didn’t cover products—and no one thought to check the supermarket shelves.

Fast forward a few decades, and the scam has scaled beautifully. A 2015 investigation by New York City’s Department of Consumer Affairs compared nearly 800 products. The result? On average, women paid 7% more than men for almost the same stuff. Toys, clothes, personal care products, senior living aids — you name it. Girls' toys cost 7% more than boys’. Women’s clothes? 8% more. Personal care products? A juicy 13% more.

And it wasn’t subtle, either. One infamous example: a red Radio Flyer scooter for boys cost $24.99. The exact same scooter, dipped in pink, was flogged to girls for $49.99. Double the price. Same wheels. Same handlebars. Different marketing department.

It was a masterclass in how to turn gender stereotypes into cash flow.

The Marketing Con Behind the Pink Tax

Here’s the bit brands won’t admit: women’s products aren’t more expensive because they cost more to make. They’re more expensive because brands can get away with it.

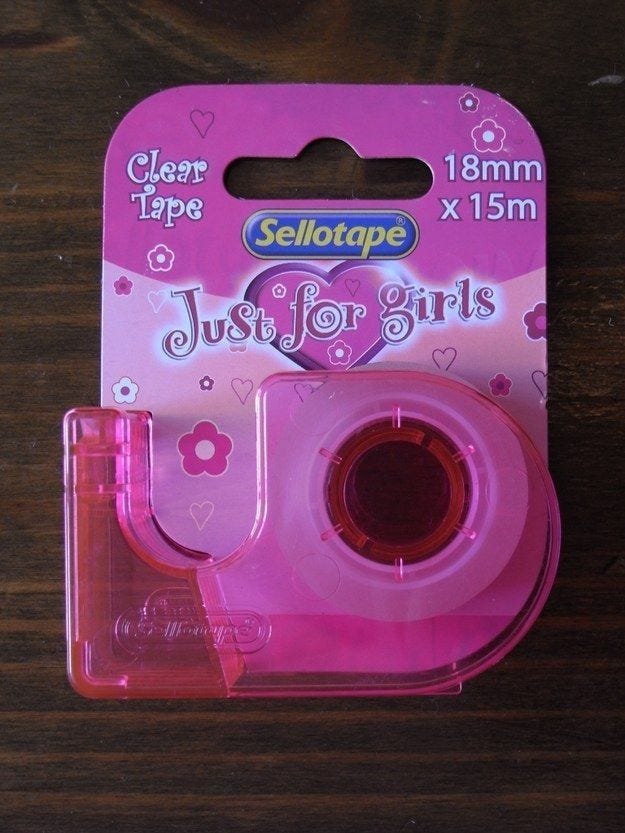

Marketing teams perfected the “Shrink it and Pink it” method years ago. Take a standard product, make it smaller, paint it pink, slap on some floral packaging, and watch the margins climb. Women’s lotions come in smaller tubes. Their shampoos are sold separately from conditioners (whereas men get 2-in-1 bottles). Women’s deodorants often cost more per gram. It’s death by a thousand scented cuts.

Brands justify this by claiming women’s products are “specialised” — more “nourishing,” more “soothing,” more “beautiful.” In reality, the ingredients lists are often identical to the men’s version, apart from a dash of lavender or the word “delicate” on the label. Consumer reports have found over and over that women are being upsold on air.

And let’s not forget how pricing psychology plays into it. Women are conditioned to believe they deserve more expensive products — that a pink razor with a “moisture strip” is a life necessity, not a marketing trick. Meanwhile, the “men’s” version — cheaper, bulkier, and blue — sits quietly on the next shelf, daring anyone to notice.

The Pushback Begins

The good news is: consumers have started to wake up.

It’s now common advice on social media for women to just buy men’s products — men’s razors, men’s body wash, men’s trainers. You get more product, better prices, and you don’t pay for someone else’s idea of what “feminine” smells like.

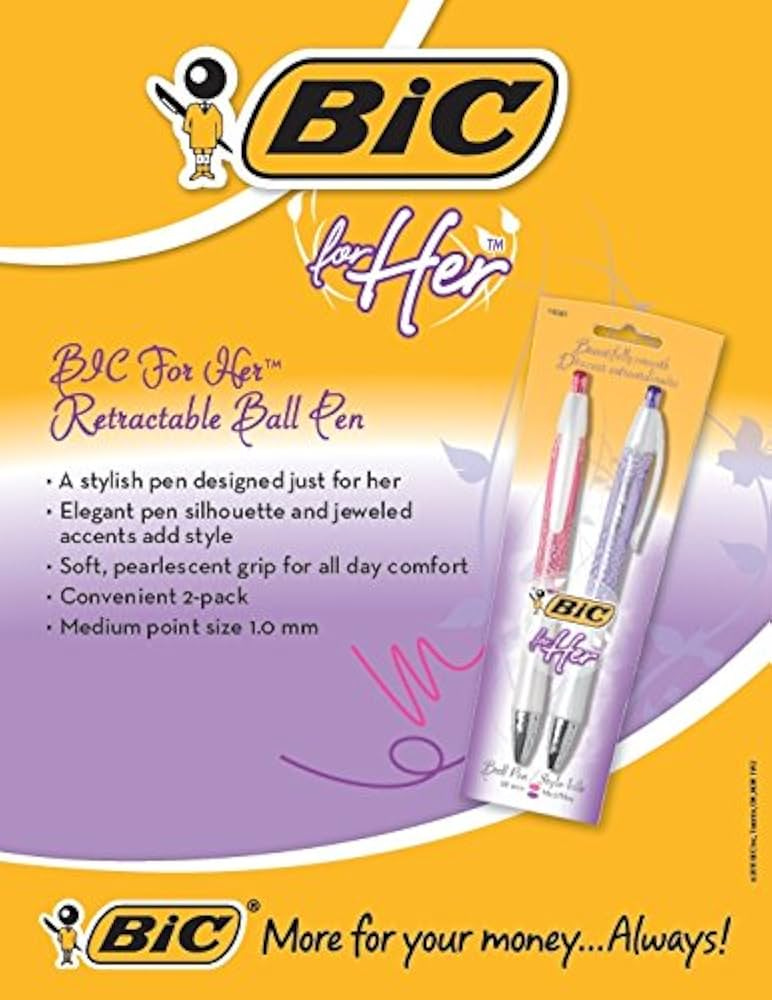

Brands who cling too tightly to pink tax pricing are also risking serious PR blowback. When BIC famously released their “Pens for Her” — literally regular pens in pastel colours, sold at higher prices — the internet dragged them through the mud so thoroughly that it became a case study in marketing hubris.

New challenger brands have spotted the gap. Companies like Billie launched pink-tax-free razor subscriptions, proudly advertising that they charge women fairly. Billie’s founder even admitted she used to buy men’s razors herself, refusing to pay the “absurd” markup on women's products.

Even some traditional giants are backpedaling. Boots in the UK, after being publicly shamed for charging more for women’s skincare and razors, slashed prices and promised reviews of all their gendered products. Target in the US reorganised its toy aisles to remove gendered signs altogether. And California passed a law in 2023 banning gender-based price differences on nearly identical products — following New York’s lead.

The writing’s on the wall: the pink tax is getting harder to hide.

Why the Pink Tax Still Persists

But if awareness is rising, why does the pink tax still exist in 2025?

Partly because brands are stubborn. Partly because consumer behaviour is hard to shift overnight. And partly because even now, price differences can be hidden inside complicated marketing.

One newer threat is algorithmic bias. Dynamic pricing models — the ones used by online shops and marketplaces — sometimes reinforce old biases. If an algorithm notices women are more likely to buy a certain type of deodorant, and less price-sensitive about it, it might quietly nudge the price upwards. No human hands necessary. The discrimination becomes baked into the machine.

Meanwhile, enforcement of pink tax bans is patchy. In California and New York, regulators can act — but companies often dodge scrutiny by making tiny tweaks to claim their products are “different enough” to justify a price gap. A moisturiser for women has “added rosewater”? Suddenly it’s not identical to the men’s version. Case closed.

And most countries don’t have clear pink tax laws yet. In the UK and the EU, consumer protection rules discourage discrimination — but there’s no explicit ban on gendered pricing. So unless there’s massive public outrage, most brands simply carry on.

Where We Go From Here

Here’s the simple truth: brands created the pink tax. They can kill it off just as easily.

Some are already moving toward gender-neutral marketing — not out of generosity, but because it sells better to Gen Z. This is the generation that grew up seeing gendered advertising as cringey. They want unisex packaging, transparent pricing, and companies that don't patronise them.

Legislation will help too. California’s Pink Tax Act has already set a precedent. If more regions follow — and there’s growing pressure on Canada, the EU, and Australia to do just that — companies will have no choice but to ditch lazy gender-based pricing once and for all.

But ultimately, the real power lies with shoppers. Every time someone refuses to pay extra for a pink razor, a bit of the scam dies. Every time a parent buys the cheaper boys' helmet for their daughter, a bit of the marketing myth crumbles.

The pink tax was never about quality. It was about marketing, greed, and a quiet assumption that women wouldn't notice. They noticed. And in 2025, they're making it very clear: enough is enough.