The U.S. vs. China: A 100-Year Trade War

From Nixon’s handshake to Trump’s tariffs, this is the full story of how America and China turned trade into a battlefield for global power.

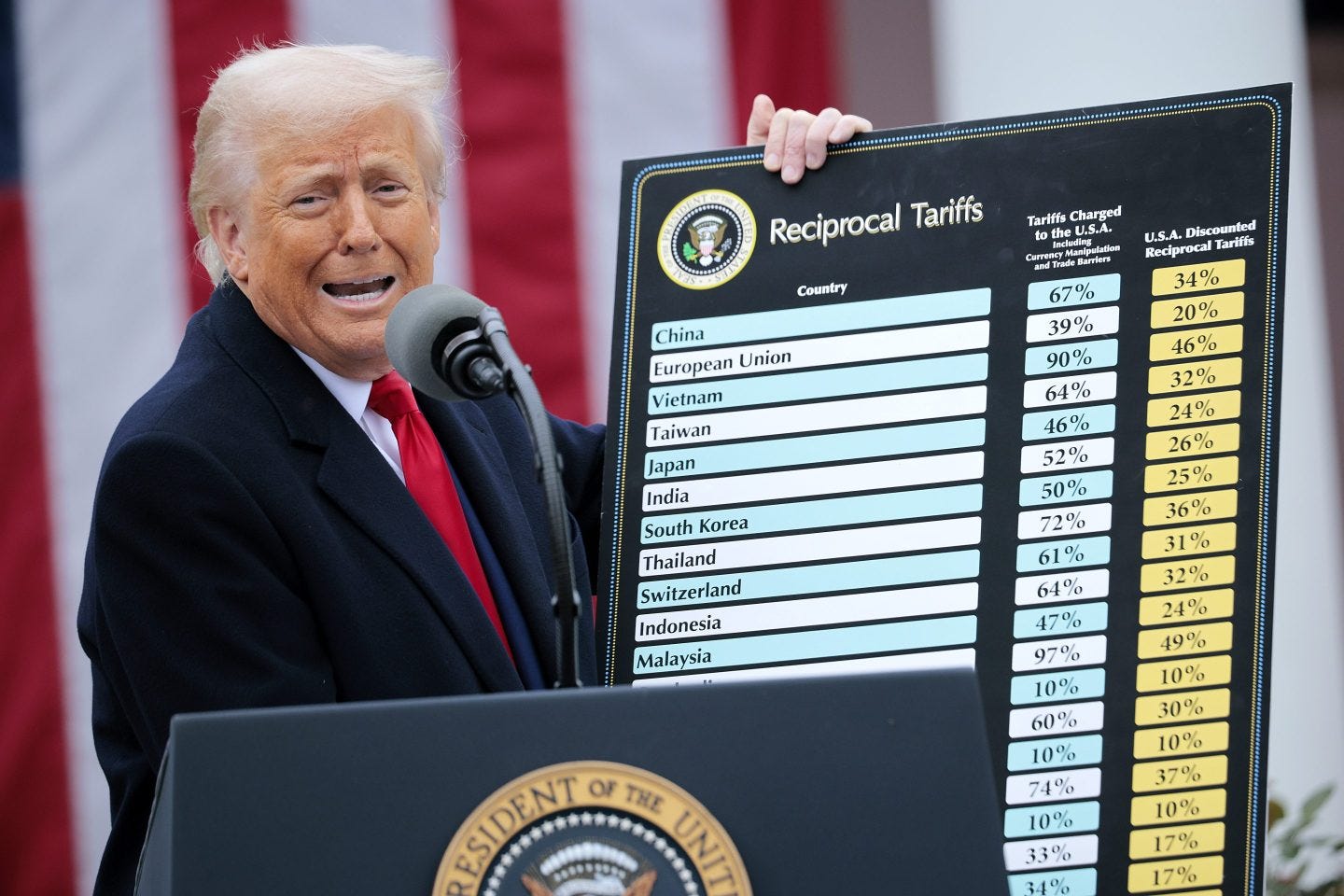

On April 2, 2025, Donald Trump declared “Liberation Day” — a full-scale tariff offensive meant to, in his words, “unshackle American workers from globalist tyranny.” The announcement landed like a policy bomb: a 10% blanket tariff on all imports, regardless of origin. But over the following days, the rhetoric and focus shifted — and it became clear that China was the real target.

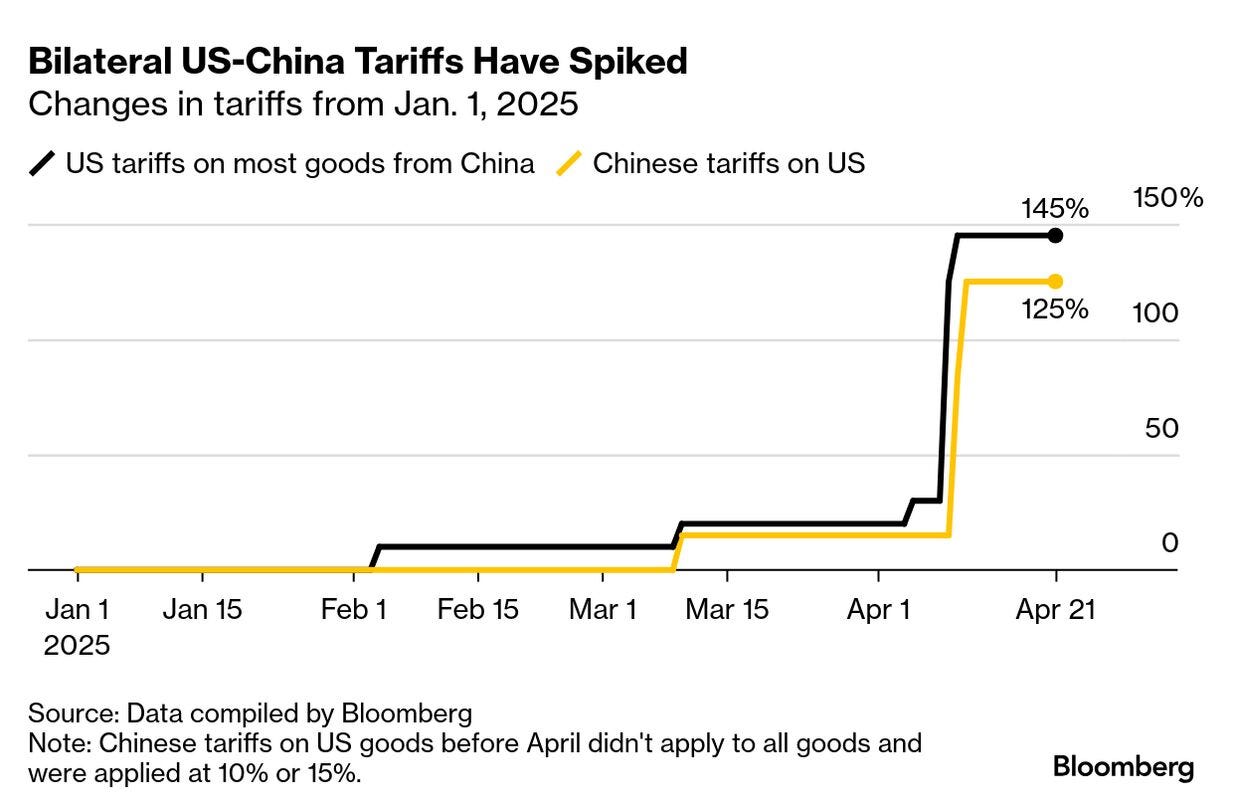

New measures hit fast: 100% tariffs on Chinese electric vehicles, 50% on semiconductors and solar panels, and 25% on critical minerals like lithium, graphite, and rare earths. China retaliated with tariffs of up to 125% on U.S. exports and further weaponised its dominance in rare earth exports.

But none of this came out of nowhere. It was the inevitable eruption of a slow-boiling economic cold war nearly a century in the making.

The Roots of a Rivalry

For much of the 20th century, the United States and China were ideological adversaries rather than trading partners. After the Chinese Communist Party took power in 1949, Washington severed diplomatic ties and imposed a sweeping trade embargo, banning virtually all commercial interaction with the newly established People’s Republic. For the next two decades, economic relations were frozen. China, meanwhile, focused on internal development under Mao’s centralised economic model, largely shunning external trade.

That impasse began to thaw in the early 1970s, driven by geopolitical shifts. With relations deteriorating between China and the Soviet Union, the U.S. saw strategic value in engaging Beijing. President Richard Nixon’s 1972 visit to China was a diplomatic earthquake — the first by a sitting American president. It resulted in the Shanghai Communiqué, in which both nations committed to normalising relations.

The process culminated in 1979 when President Jimmy Carter formally recognised the People’s Republic of China. That same year, the two countries signed the U.S.–China Trade Agreement, lifting the long-standing embargo and granting China most-favoured-nation (MFN) trading status for the first time since 1949. At the time, bilateral trade was virtually non-existent — totalling just $4.8 million in 1979.

It would not stay that way for long. Within a decade, trade volumes ballooned into the billions, ushering in a new era of interdependence that would eventually turn into rivalry.

From Opening Up to Selling Out

During the 1980s and 1990s, Deng Xiaoping’s policy of “reform and opening up” transformed China from a closed, centrally planned economy into a low-cost industrial powerhouse. The government created Special Economic Zones (SEZs), relaxed controls over private enterprise, and opened the door to foreign direct investment. Multinational corporations — especially from the United States — were quick to take advantage. Enticed by low wages, minimal environmental regulation, and state-backed infrastructure, American companies began offshoring production to Chinese factories at scale.

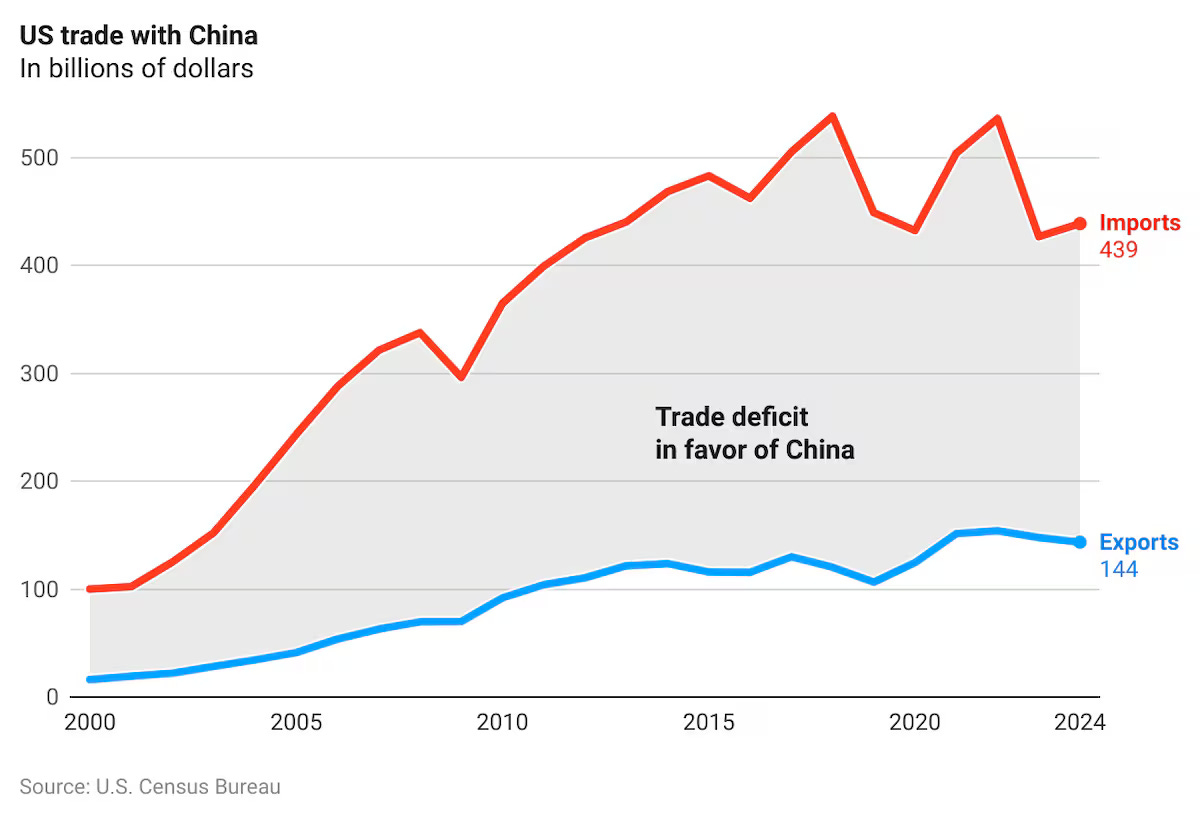

The pace of integration accelerated in 2001 when China joined the World Trade Organisation (WTO), following years of negotiation and promises to liberalise its economy and respect intellectual property. Membership meant lower tariffs and easier access to global markets — and U.S. firms surged in. That same year, American imports from China totalled $102 billion. By 2019, that figure had more than quadrupled to over $449 billion, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

For Wall Street, it was a windfall. Corporations slashed costs. Investors pocketed record profits. American consumers, meanwhile, were flooded with cheaper goods — from electronics to clothing. But for American manufacturing towns, the consequences were dire. As factories closed and jobs disappeared, entire communities in the Rust Belt and beyond were left behind — a phenomenon later dubbed the “China shock.”

The China Shock Hits Home

Economists now refer to it as the “China shock” — a seismic shift in global trade that devastated large parts of American manufacturing. The term comes from a widely cited study by economists David Autor, David Dorn, and Gordon Hanson, which documented how rising Chinese import competition after 2001 led to sharp and sustained job losses across the United States. According to the National Bureau of Economic Research, between 1999 and 2011, the U.S. lost 2.4 million manufacturing jobs directly due to the surge in Chinese imports.

Entire regions — especially in the Midwest and South — saw factories shuttered, wages stagnate, and employment opportunities vanish. While consumers enjoyed cheaper goods, the social and economic cost in former industrial strongholds was immense. Many communities never recovered.

Meanwhile, the U.S. trade deficit with China ballooned, rising from $83 billion in 2001 to $295 billion by 2011, a nearly fourfold increase. To critics, this wasn’t free trade — it was a one-sided arrangement that hollowed out the American working class while strengthening a geopolitical rival. China, once welcomed as a partner in globalisation, was increasingly viewed as an economic predator playing by its own rules.

Trump’s First Trade War

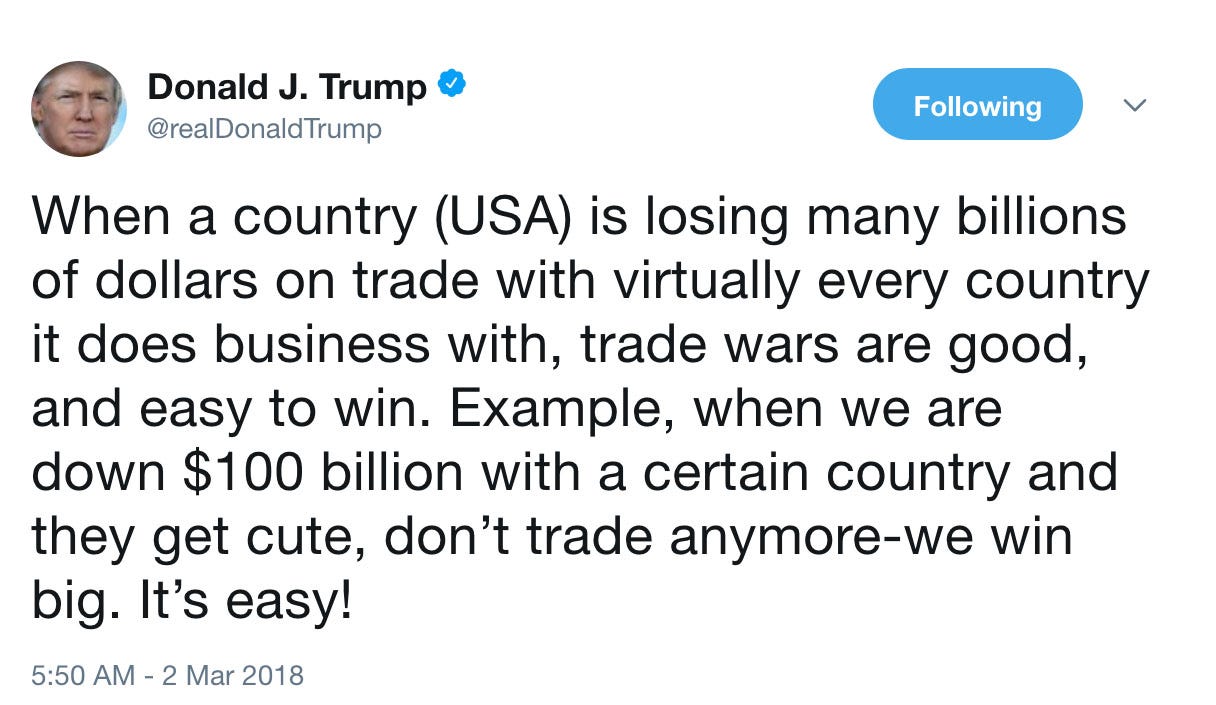

When Donald Trump entered office in 2017, he made it clear that business as usual with China was over. Campaigning on a promise to reverse decades of perceived economic surrender, Trump pledged to bring jobs back to the United States and reduce the ballooning trade deficit with Beijing. In 2018, he launched a full-blown trade war — one of the most aggressive moves in modern U.S. economic policy.

Citing unfair trade practices, intellectual property theft, and forced technology transfers, the Trump administration used Section 301 of the Trade Act of 1974 to justify a wave of tariffs on Chinese imports. The first round imposed 25% duties on $50 billion worth of goods, targeting industrial sectors like aerospace, robotics, and machinery. By the end of the escalation, the U.S. had levied tariffs on over $360 billion in Chinese products.

China retaliated with tariffs of its own, hitting $110 billion worth of American exports — with a focus on politically sensitive sectors like agriculture, automotive, and chemicals. U.S. farmers, particularly soybean producers, bore the brunt of the countermeasures. The Trump administration was forced to authorise over $28 billion in farm subsidies to offset the losses.

The broader impact was felt across the economy. Disrupted supply chains led to uncertainty for businesses, while American consumers were left holding the bag. A 2020 analysis by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York estimated that the tariffs cost U.S. households $1.4 billion per month in higher prices, with the burden falling disproportionately on lower-income families.

Despite the economic turbulence, Trump’s supporters argued that the confrontation was long overdue. For them, it was a necessary correction after decades of appeasement. For critics, it was an expensive and chaotic gamble that punished American businesses and consumers more than it disciplined Beijing.

Biden’s Tech Cold War

Joe Biden didn’t reverse Trump’s trade war — he reloaded it with a new target: China’s technological ambition. While the Trump administration fixated on trade imbalances, steel, and soybeans, Biden shifted the battlefield to semiconductors, artificial intelligence, and high-end manufacturing — the future of global power.

In October 2022, the U.S. Department of Commerce introduced sweeping export controls designed to block China’s access to advanced computing chips and the equipment used to manufacture them. The rules prohibited U.S. companies from supplying high-end semiconductors or chipmaking tools to Chinese firms — and barred American citizens from supporting China’s chip development in any capacity.

That same year, Biden signed the CHIPS and Science Act, a bipartisan law committing $52.7 billion in federal subsidies to boost domestic chip manufacturing, research, and workforce development. The goal was clear: reduce dependency on Asia, rebuild America’s chipmaking capability, and prevent China from surpassing the U.S. in critical technologies.

Why the urgency? Because semiconductors are the new oil. They power everything from iPhones and F-35 fighter jets to AI servers and nuclear submarines. Control the chips, and you control the world.

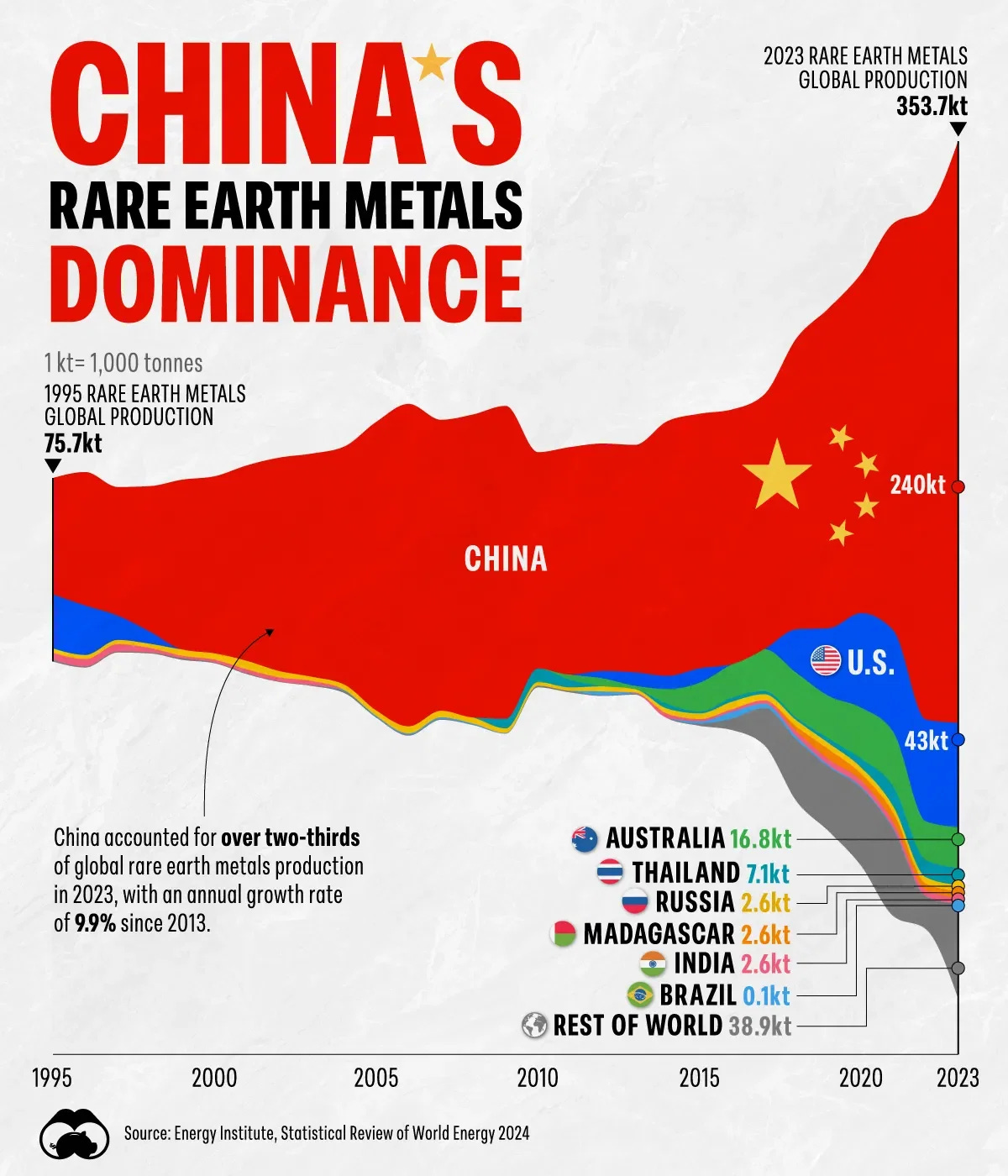

China responded in kind — not with tariffs, but with mineral leverage. In 2023, Beijing announced restrictions on the export of gallium and germanium, two critical metals used in semiconductors, solar panels, and military-grade electronics. And when tensions escalated again in 2024, China tightened its grip on rare earths — a group of 17 elements essential for electric motors, wind turbines, lasers, and missile systems.

The U.S. relies heavily on Chinese supply for these materials. In 2021, 78% of U.S. rare earth imports came from China, according to the U.S. Geological Survey. Put bluntly: if Beijing turns off the tap, the Pentagon and Tesla alike would feel the squeeze.

What began as a tariff spat had morphed into something far more dangerous — a technological arms race, with minerals and microchips as the ammunition.

The Great Divorce That Wasn’t

For years, U.S. politicians railed against China and called for “decoupling” — severing economic ties in the name of national security and industrial resilience. In boardrooms, executives softened the language, opting instead for “de-risking” — a polite euphemism for diversifying supply chains without blowing up the entire global order.

But for all the tough talk, very little changed.

In practice, China remained indispensable. Its manufacturing infrastructure was not only vast, but hyper-efficient. From raw material extraction to final assembly, no other country could match its scale, cost, and logistics speed. Even companies that pledged to diversify — Apple, Tesla, Nike — continued to rely heavily on Chinese factories.

Yes, some production shifted to Vietnam, India, and Mexico. But the volumes were limited, and relocating high-tech or tightly integrated supply chains proved far more complex and expensive than anticipated.

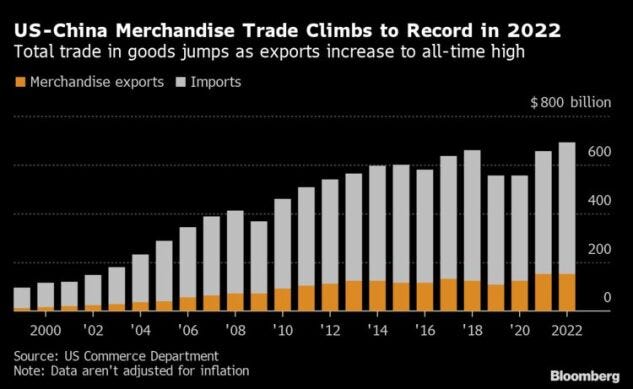

The numbers told the real story: U.S.–China goods trade reached a record $690.6 billion in 2022, making China America’s largest trading partner for goods that year. That included $536.3 billion in Chinese imports and $154.3 billion in U.S. exports — a staggering trade imbalance that belied the political rhetoric.

So while lawmakers branded Beijing an existential threat, American businesses kept shipping containers full of electronics, machinery, furniture, and clothing across the Pacific.

2025: Tariffs, Chips, and the New Cold War

That brings us to 2025. On 2 April, Donald Trump declared what he called “Liberation Day” — a sweeping economic offensive meant to “restore American independence” from foreign manufacturing. His administration unveiled a universal 10% tariff on all imports, alongside targeted penalties: 100% on electric vehicles, 50% on semiconductors, and 25% on critical minerals such as lithium, cobalt and graphite.

The tariffs weren’t merely punitive — they were ideological. Liberation Day marked a pivot away from decades of liberalised global trade and towards economic nationalism, reindustrialisation, and strategic self-reliance. Trump didn’t just want to hit Chinese exports. He wanted to overhaul the structure of global commerce.

The effects were immediate. U.S. electric vehicle prices surged as domestic automakers scrambled to source non-Chinese batteries and parts, many of which remain deeply embedded in global supply chains. Semiconductor firms were caught off guard, forced to reroute procurement networks or swallow rising costs. Clean energy projects stalled, as solar panel imports and mineral inputs became more expensive. Inflation, already stubborn, crept upward as businesses passed import costs onto consumers — with analysts projecting a 4–5% spike over the remainder of the year.

China responded swiftly. It imposed up to 125% tariffs on U.S. goods, particularly targeting agriculture, aerospace, and high-value manufacturing sectors. More strategically, it enacted fresh restrictions on exports of rare earth elements — minerals like neodymium, dysprosium and terbium that are critical to electric motors, wind turbines, missile guidance systems, and other advanced technologies. With China still dominating 90% of the world’s rare earth refining capacity, the U.S. found itself acutely vulnerable.

Despite the tough talk about “bringing jobs home,” reshoring production remains slow, costly, and constrained by infrastructure. America still lacks the facilities to refine many critical minerals domestically, and efforts to rebuild domestic chip manufacturing — even with CHIPS Act funding — are years from bearing full fruit. As Reuters noted, the strategy risks short-term pain without guaranteed long-term gain.

So, who’s winning? Certainly not consumers, who are already paying more. Not global markets, which are increasingly jittery about supply disruptions and trade fragmentation. American manufacturers are facing margin pressure. And while China has been hit hard, it is accelerating its push for technological self-sufficiency and deepening trade ties with the Global South — insulating itself from future U.S. pressure.

Liberation Day was never just about tariffs. It was about drawing a line in the sand. And that line now runs straight through the heart of the global economy.

Conclusion: Trade War or Economic Cold War?

Let’s be clear: this isn’t just a trade spat — it’s the economic front of a new cold war. Tariffs, chips, critical minerals, and global influence are the weapons. The goal? Control over the industries and rules that will define the 21st-century economy.

The U.S. aims to secure dominance in key technologies and insulate its supply chains from Chinese leverage. China wants to break free from Western tech dependence and build its own industrial empire. Both see economic strength as national power. The rest of the world? Stuck in the middle.

Trump’s “Liberation Day” wasn’t just about imports — it was a direct hit on Beijing’s industrial engine. China’s retaliation confirmed what many feared: this is no longer about trade policy. It’s a turning point in a decades-long rivalry that began with Nixon’s 1972 handshake and never really cooled.

After a century of shifting between cooperation and conflict, the gloves are off. Two superpowers are now openly weaponising economics — and “Liberation Day” may be just the start.